What Happened to Egypt’s “Arab Spring”?

Just over three years ago, Egypt was ruled by Hosni Mubarak’s autocratic police-state. During the “Arab Spring,” crowds massed in Tahrir Square to protest the Mubarak regime, and he was soon removed from his throne. Then Mohammad Morsi, aligned with the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood, took power. He sought to establish his own kind of tyrannical control. The military toppled him. Now, a new military-backed strongman, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, heads Egypt. The country seems poised for another Mubarak-esque period. Egypt has swung from one kind of tyranny (dictatorship) to another (Islamist rule) — and back again. Why?

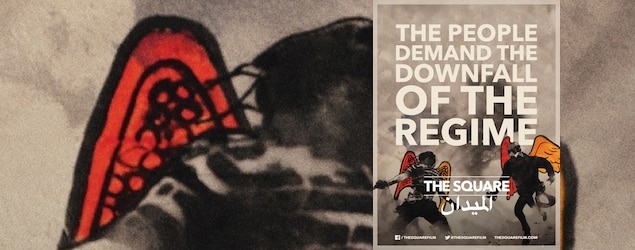

By way of answering that, I’d single out two salient factors. First, the military establishment and the Islamist factions are deeply entrenched, and in effect dominate the political scene. The military wields enormous control over the apparatus of the state. The religious groups, able to couch their positions in moral terms, can set the terms of debate. One result is that the few secular-oriented groups seeking some modicum of freedom are easily marginalized (as I argue here). So the prospects for fundamental change — an enormous undertaking that would require many years — were dismal. A second factor is related to that: the better elements among the protesters in Tahrir Square were hamstrung by lacking a well-defined, positive ideological vision. You can see that point emerge in a riveting, poignant documentary, “The Square.” (The film can be watched on Netflix, and it’s definitely worthwhile.)

The film tracks a politically diverse group of friends united by outrage, standing together in the massive protests at Tahrir Square. What lends the film its narrative power is that it enables us to listen to them, uncensored by the state. For example, we sit next them in the living room of an apartment where the friends gather to track the news and make plans and to argue. The fall of Mubarak fills them with elation, the subsequent rise of the Muslim Brotherhood, gloom. When the military reasserts control in summer 2013 — opening fire on crowds with live ammunition and mowing down protestors with armored vans — the sheer brutality is overwhelming.

Dejected and pensive, one of the protesters in the film reflects on the turmoil. Thinking out loud as much as addressing the documentary crew, he points out that the protesters were united against the Mubarak regime, and that enabled them to bring together many different factions at the Square — but what, exactly, were they for? Without that, he muses, how far could they get.