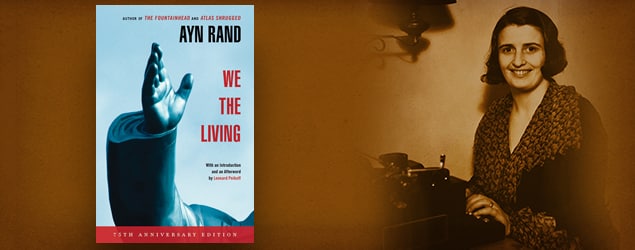

We the Living: Ayn Rand’s Anti-Egalitarian Novel

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the publication of Ayn Rand’s first novel, We the Living. In her foreword to the novel, Rand explains that although the book is set in 1920s Soviet Russia, We the Living is not a historical novel: it “is a story about Dictatorship, any dictatorship, anywhere, at any time” and its goal is to show what “the rule of brute force does to men and how it destroys the best.”

With its focus on how dictatorships destroy “the best” individuals, We the Living is a quintessentially anti-egalitarian novel. Egalitarianism is the doctrine that human beings should be made equal in every important respect — including, notably, equal in economic outcome. At a time when egalitarian ideas are being peddled by leading politicians (Barack Obama, Bernie Sanders) and intellectuals (Paul Krugman, Thomas Piketty), Rand’s book remains as relevant as ever.

In We the Living, Andrei Taganov defends the communist system on the grounds that it will equalize society by lifting everyone up to the level of the best. But as my colleague Onkar Ghate explains in his contribution to Robert Mayhew’s excellent collection Essays on Ayn Rand’s “We the Living”, that is not what communism — and egalitarianism more broadly — achieves or is intended to achieve:

Rand, when analyzing the Left years later, commented that the goal of “equal prosperity” for all gave superficial plausibility to the ideology of collectivism. If Andrei’s error in being seduced by communism is an honest error, as the novel portrays it to be, then this superficial plausibility is a significant part of the explanation. But the fact remains that the egalitarianism at the heart of collectivism cannot, and is not meant to, lift people up. As Rand wrote more than thirty years after publishing We the Living, equality of results (as opposed to equality of individual rights before the law) could be achieved in only two ways: “either by raising all men to the mountaintop — or by razing the mountains.” The first method, however, is metaphysically impossible, since individuals have different attributes and abilities and make different choices. So the only actual meaning of a crusade for equality of results is a crusade to level society by pulverizing the mountains. Not surprisingly, therefore, this is what is portrayed in page after page of We the Living.

Today’s egalitarian critics of economic inequality are not generally advocates of dictatorship. Piketty, author of the 2014 blockbuster Capital in the Twenty-First Century, may have titled his book as an homage to Karl Marx, but he is not calling for a socialist revolution. He accepts the desirability of a “market economy,” but wants to “temper” unequal outcomes, mainly through tax policy: top marginal income tax rates as high as 80 percent, an annual wealth tax of up to 10 percent, and an inheritance tax of 80 percent.

But as Yaron Brook and I argue in Equal Is Unfair, although inequality critics like Piketty eschew the means advocated by their totalitarian forebears, they share the same goal: to bring down the successful.

Take Piketty’s tax proposals, for instance. Are these taxes to be used to help lift up those below the top? Not according to Piketty. In every case, Piketty acknowledges that “these very high brackets never yield much” in the way of tax revenues. That is not the point. The point, he says, is “to put an end to such incomes and large estates.”

What We the Living shows is the moral bankruptcy at the heart of all collectivist doctrines, whether the advocates seek to expand the regulatory-welfare state or to establish a full-fledged dictatorship. Collectivists are not champions of “the people” or “the poor”—but enemies of the best among men and the best in each man.

We the Living is first and foremost a captivating and deeply moving story. But it is also a novel of ideas: if you want to understand today’s debate, the book and its ideas are well worth grappling with.

For more news on ARI’s fight for a rational culture, subscribe to Impact Weekly.