Romantic Love

To celebrate Valentine’s Day, we asked Jeff Britting, curator of the Ayn Rand Archives, to supply us with images and text from an article he wrote that originally appeared in the Ayn Rand Institute’s newsletter, Impact, in 2012. The feature commemorates Valentine’s Day, discusses Ayn Rand’s view of romantic love and the bond between Ayn Rand and her husband, Frank O’Connor. The images that accompany this feature are from the Archives collection.

* * *

Among the personal papers of Ayn Rand is a single valentine greeting, dated February 12, 1970. It was addressed to Ayn Rand from her young friend and fellow stamp collector, Tammy Vaught, daughter of the family who hosted Miss Rand and her husband, Frank O’Connor, while they attended the Apollo 11 launch at Cape Kennedy. Miss Rand accepted Tammy’s greeting, replying: “It has been a long time since anyone sent me a Valentine, and it pleased me very much.”

The printed valentine is an American tradition, whose European origin is rooted in pagan antiquity, very likely as a celebration of fertility. Today, the exchange of valentines occurs on February 14, a day set aside to celebrate romantic love.

As her works make clear, Miss Rand regarded romantic love as a profound value. Elaborating on the nature of one’s response to a romantic partner, she writes:

It is with a person’s sense of life that one falls in love — with that essential sum, that fundamental stand or way of facing existence, which is the essence of a personality. One falls in love with the embodiment of the values that formed a person’s character, which are reflected in his widest goals or smallest gestures, which create the style of his soul — the individual style of a unique, unrepeatable, irreplaceable consciousness. . . . [W]hen love is a conscious integration of reason and emotion, of mind and values, then — and only then — is it the greatest reward of man’s life. – “Philosophy and Sense of Life” in The Romantic Manifesto

Miss Rand achieved such a bond with her husband, Frank O’Connor. Nowhere was their deep affinity for each other more evident than in their responses to each other’s creative work.

Reflecting on her husband after his death in 1979, Ayn Rand said:

We were really, I would say, spiritually, collaborators. I have always told him I could not have written without him. He denies it; he thinks I would have broken through, but I know too well, and perhaps that’s the only tribute I can pay him with my readers, that it is impossible to hold a benevolent universe view consistently, the way I had to hold it to write what I have written, and to project an ideal life, when the actual life around us was getting worse and worse; when it was all going in the direction of Ellsworth Toohey, and I was writing about John Galt. I couldn’t have done it if it weren’t for the fact that I knew one person who did live up to my heroes and my view of life. – Objective Communication course; Q&A, 1980

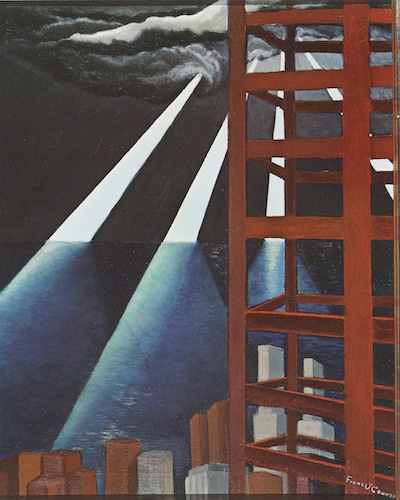

Perhaps Miss Rand’s most dramatic and public expression of her view is in the twenty-fifth-anniversary edition of The Fountainhead. The introduction explains how her husband helped her through a night of extreme discouragement. Thereafter, she broke her rule against book dedications, dedicating the work to her husband, who had saved the novel-in-progress. Fittingly, the twenty-fifth-anniversary edition displays an oil painting by Frank O’Connor titled Man Also Rises.

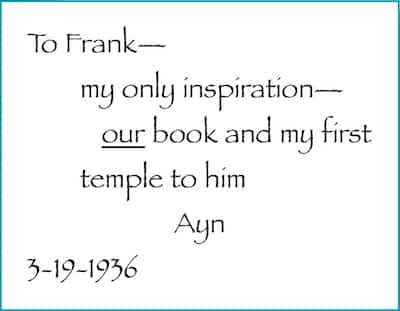

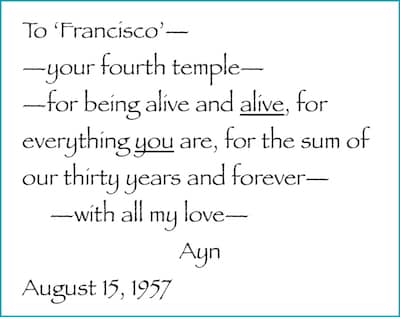

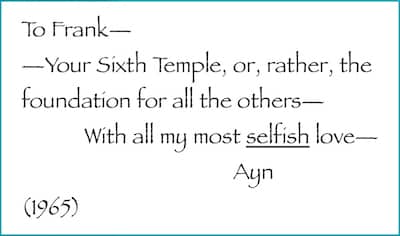

There are also personal dedications Ayn Rand inscribed in the private copy she presented to her husband of each book she wrote. Miss Rand’s goal in fiction was the portrayal of an ideal man. In her husband, Frank O’Connor, she found the qualities of character that made the depiction of a Howard Roark and John Galt possible. And her book inscriptions reflect her gratitude. The inscriptions begin in 1936 with her first novel, We the Living. As tokens of appreciation, these inscriptions celebrate a lifelong “spiritual collaboration.”

The text of the inscriptions can be found below and are offered without further comment.