Cheering for the Charlie Hebdo Attacks: The Shape of Things to Come?

Ten years ago last week, the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten published twelve cartoons related to Islam. The aim was to gauge a seemingly growing climate of self-censorship in Europe. The ensuing crisis went global.

By looking at the erosion of free speech in Europe, you could see markers of what to expect here. European self-censorship, my colleague

Onkar Ghate argued at the time, was coming to America. By the spring of 2006, Borders Books and Waldenbooks announced that they would not stock an upcoming issue of Free Inquiry magazine, because it reprinted some of the notorious cartoons.

The fear was pervasive. Major American news outlets refused to reprint the cartoons, even in reports on the rioting and deaths related to the cartoons crisis. Some years later, Yale University Press published a scholarly book analyzing the cartoons crisis — but decided just before going to press to excise every one of the 12 cartoons, along with other images.

In Europe, filmmakers, artists, and writers had been threatened, attacked, murdered. Such threats and attacks were occurring here too.

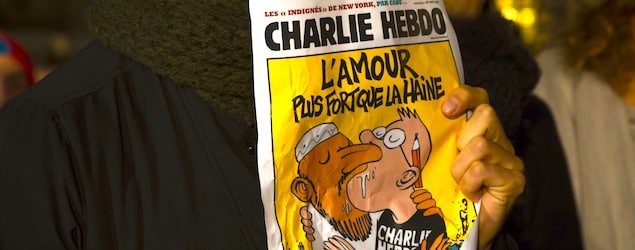

In January 2015: Islamist gunmen massacred journalists at the magazine Charlie Hebdo in Paris. In May 2015: Islamists tried to attack a free speech event in Garland, Texas. Writing on Voices for Reason, Steve Simpson pointed out that the destruction of freedom of speech succeeds in large part because of the continuing appeasement in the West of those who resort to threats and violence. Steve’s post, incidentally, was published five days before the Garland attack.

Although Europe is farther along, the trend is clear. That’s what came to mind when I read Brendan O’Neill’s account of a debate at the prestigious Trinity College, Dublin, in Ireland, on the right to be offensive. He writes:

I was on the side of people having the right to say whatever the hell they want, no matter whose panties it bunches. The man on the other side who implied that Charlie Hebdo got what it deserved, and that the right to offend is a poisonous, dangerous notion, was one Asghar Bukhari of the Muslim Public Affairs Committee.

It is depressing, but not surprising, that Bukhari’s view is taken seriously. What I found bone-chilling is the reaction of students in the audience. They listened intently to Bukhari’s case. Some cheered.

This is how screwed-up the culture on Western campuses has become [writes O’Neill]: I was jeered for suggesting we shouldn’t ban pop songs; Bukhari was cheered for suggesting journalists who mock Muhammad cannot be surprised if someone later blows their heads off.

One audience at one debate at one university in one city: obviously that’s at most a data point, not a trend. But do the attitudes of these students — whom O’Neill describes as non-fringe, young, and with-it — reflect broader trends in Europe? Quite possibly.

What does that imply for the future of free speech in Europe — and here?

* * *

If you’re new to Voices for Reason, the following posts, articles, and videos lay out ARI’s principled defense of the freedom of speech:

- “The Assault on Free Speech” by the Editors

- “Freedom of Speech: We Will Not Cower” by Onkar Ghate

- “Attacks on Free Speech Come to the U.S.” by Steve Simpson

- “The Fear to Speak Comes to America’s Shores” by Onkar Ghate

- Charlie Hebdo, the West and the Need to Ridicule [Video] by the Editors

- “#JeSuisCharlie, but for How Long?” by Elan Journo

- Freedom of speech, Islamophobia and the Cartoons [Podcast] by Elan Journo