Ayn Rand’s Handwritten Notes on Atlas Shrugged

October 10 is the 60th anniversary of the publication of Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand. To commemorate that event, we asked Jeff Britting, curator of the Ayn Rand Archives, to supply us with images and text from one of the many exhibits he has mounted over the years, this one devoted to Rand’s handwritten notes and drafts for the novel, which was published in 1957.

* * *

Ayn Rand described the theme of Atlas Shrugged as “the role of the mind in man’s existence — and, as a corollary, the demonstration of a new moral philosophy: the morality of rational self-interest.” The idea for the novel occurred to her in 1943, while discussing the philosophy of The Fountainhead with an acquaintance who insisted that Rand was obligated to enlighten her readers with a nonfiction version of her ethical philosophy. Rand countered she had already fulfilled the obligation and that her case was clear to any attentive reader of her fiction. However, she wondered aloud, “What would happen if every creative person went on strike against such obligations?” That, she exclaimed, would make a good novel. After the discussion ended, [her husband Frank] O’Connor, who was in the room at the time, turned to her and said: “It would make a good novel.”

Rand thought that “The Mind on Strike” would be a relatively short work dealing with economics, and that it would “illustrate [The Fountainhead’s] philosophy in action [and] merely show that capitalism and the proper economics rest on the mind.” But as she further examined the mind’s role in human existence, the scope of the novel expanded. Eventually, the finished novel integrated a wide range of topics, including metaphysics, politics, and romantic love. She thought the novel would require two years to write; instead, it took fourteen years. The Fountainhead, as she later put it, was merely an overture to Atlas Shrugged.

The story of Atlas Shrugged concerns men and women of ability in all fields, who are oppressed by a collectivist world that refuses to recognize their value. The background is modern industrial civilization. When the story opens, New York City is crumbling . . . . living conditions are getting worse. The world’s generator is running low, but no one knows why. Against this backdrop, Rand would present and dramatize her entire philosophy.

From Ayn Rand

by Jeff Britting

The Overlook Press, 2004

The manuscript pages on display here cover a period of twelve years. They include the earliest written notes on the novel (January 1, 1945) and the final handwritten page of the novel (March 20, 1957). These selections contain some of the earliest extant pages of the manuscript. What emerges from these selections is the breadth of Ayn Rand’s philosophical thinking. Those familiar with the published novel will find many recognizable ideas in earlier forms. Those unfamiliar with Atlas Shrugged will find an introduction to the novel’s philosophical scope and literary means.

An advisory to readers unfamiliar with Atlas Shrugged: the pages displayed here contain “plot spoilers,” i.e., details that will diminish the suspense of the story. Further, these pages contain provisional statements of ideas presented out of their original context. The definitive statement of Ayn Rand’s ideas can be found in the many books, essays and periodicals that she published (or approved) during her lifetime.

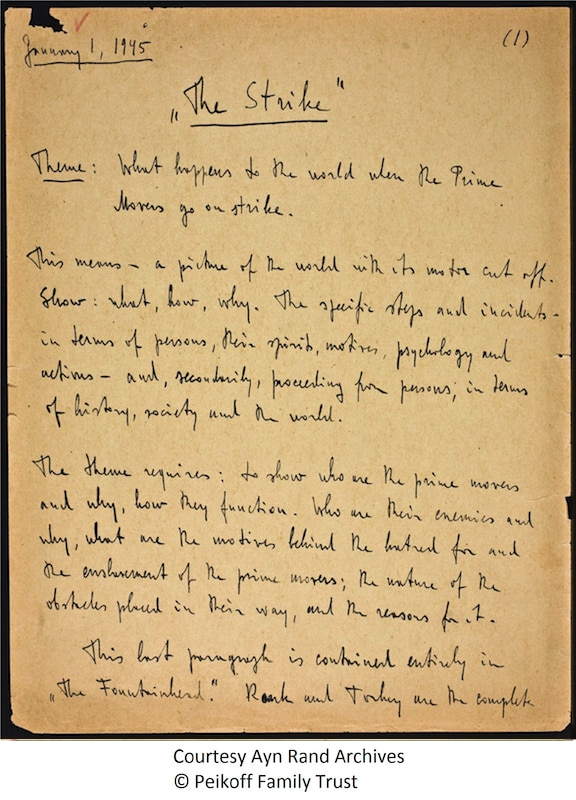

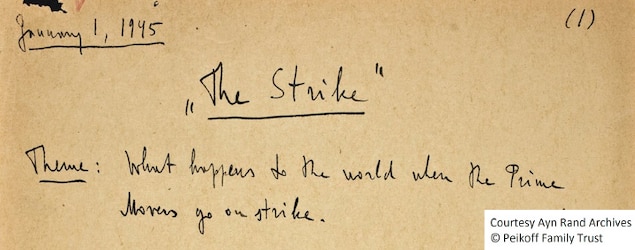

January 1, 1945

January 1, 1945, “The Strike,” p. 1

Handwritten notes on Atlas Shrugged

Reproduction on paper

Ayn Rand Archives

From the earliest extant notes stating the theme and meaning of “The Strike,” the original title of Atlas Shrugged.

In the 1940s, strikes initiated by organized labor were a well-known tactic of the American liberal left.

Rand thought that it would be both dramatic and ironic to present a strike by industrialists — the “prime movers” — against a moral code that branded them as evil exploiters. Eventually, Rand dropped the original title, “The Strike,” as too journalistic sounding.

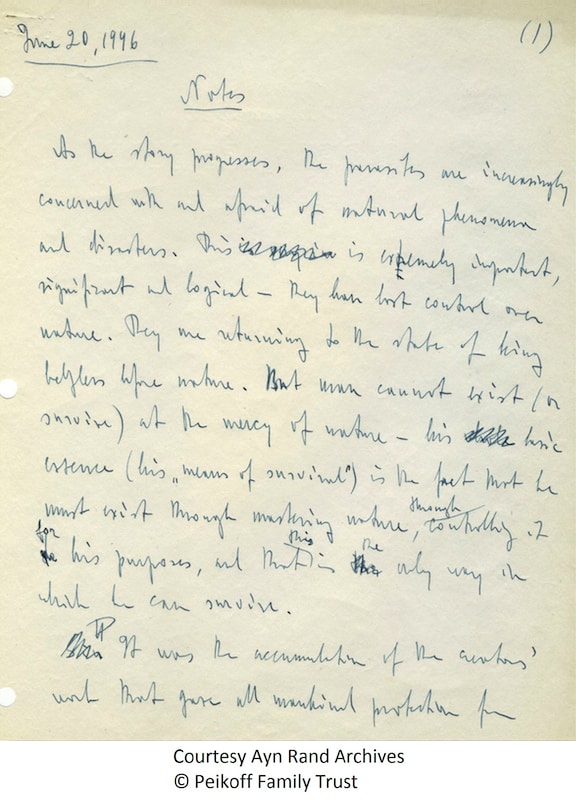

June 20, 1946

June 20, 1946, Notes, p. 1

Handwritten notes on Atlas Shrugged

Reproduction on paper

Ayn Rand Archives

This note concerns Rand’s view of man and his relationship to physical nature. As depicted in the novel, “the parasites,” i.e., those who feed off of industrialists while morally condemning them, are beginning to live in fear of “natural phenomena and disasters.” This note presents an idea first presented in The Fountainhead but expanded in Atlas Shrugged: that “man cannot exist (or survive) at the mercy of nature — his basic existence (his ‘means of survival’) is the fact that he must exist through mastering nature, through controlling it for his purposes . . .”

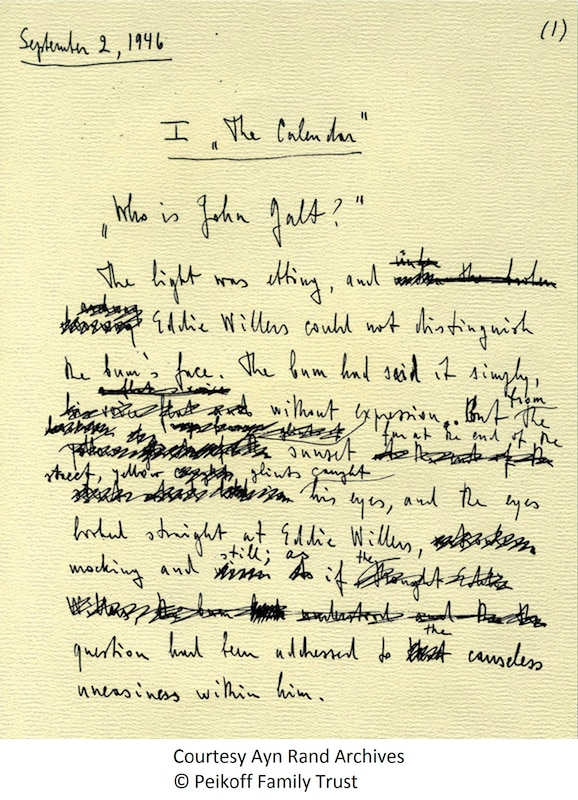

September 2, 1946

September 2, “The Calendar,” p. 1

Handwritten notes on Atlas Shrugged

Reproduction on paper

Ayn Rand Archives

The opening page of the novel is dated September 2, 1946. The expression “Who is John Galt?” — which occurs throughout the novel — evokes the despair and futility of a world in decline.

Rand wrote her fiction in longhand. After a typist created a typescript of each sequence, Rand further revisions by hand. Of the more than 12,000 pages contained in the final handwritten manuscript, she estimated that each page was rewritten, on average, five times.

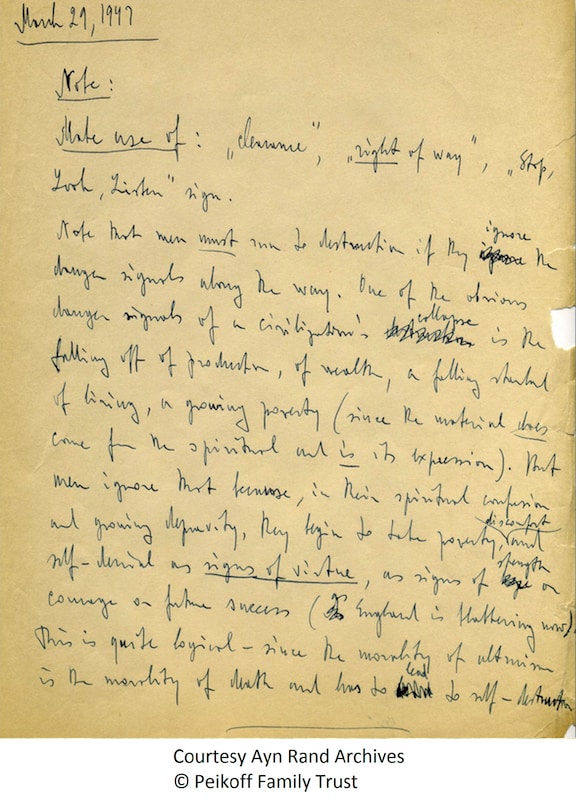

March 29, 1947

March 29, 1947, Note:

Handwritten notes on Atlas Shrugged

Reproduction on paper

Ayn Rand Archives

In this note Rand considers railroad language as a means to communicate symbolic “danger signals.” Throughout the story the phrase “Stop, Look, Listen” calls the reader’s attention to the “poverty, discomfort and self-denial” of the present. However, as presented in the novel, these signals of collapsing civilization are, in fact, considered “signs of virtue” by the intellectual status quo. Historically, the moral philosophy that regards poverty and self-denial as virtuous is altruism. Rand defined altruism as the view that

“man has no right to exist for his own sake, that service to others is the only justification of his existence, and that self-sacrifice is his highest duty, virtue and value.”

(Philosophy: Who Needs It, 1982)

The final line of the note ends with Rand’s statement that altruism is “the morality of death.” As the novel unfolds, Rand dramatizes the alternative, which she calls “the morality of life.”

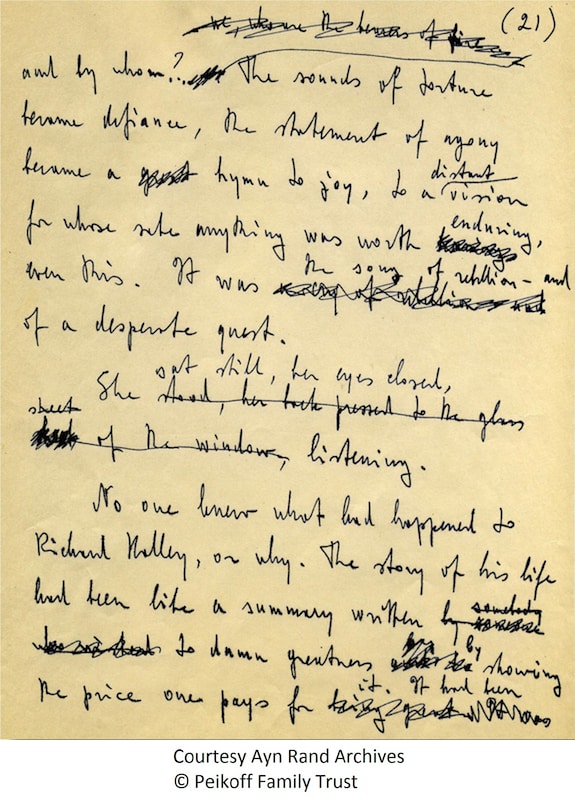

July 14, 1948

July 14, 1948, p. 21

Handwritten notes on Atlas Shrugged

Reproduction on paper

Ayn Rand Archives

This 1948 page is from the sequence introducing Dagny Taggart, the operational vice-president of Taggart Transcontinental. Dagny is a businesswoman of outstanding ability who struggles to keep her railroad in operation despite mounting government intervention. This page depicts Dagny’s affirmative response to the music of her favorite composer, Richard Halley. Halley has disappeared mysteriously at the height of his fame. Soon Dagny discovers a pattern of similar disappearances and wonders if a destroyer is removing the men of ability from the world.

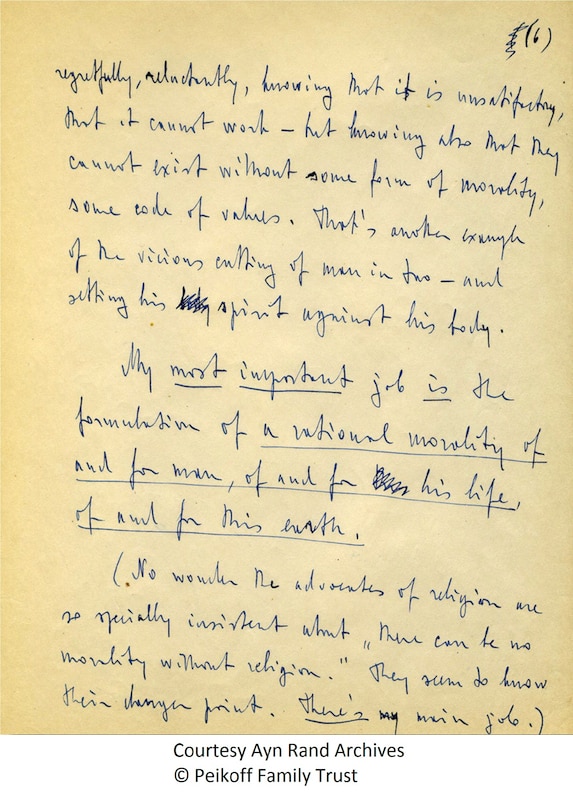

October 6, 1949

October 6, 1949, p. 6

Handwritten notes on Atlas Shrugged

Reproduction on paper

Ayn Rand Archives

The underlined sentence in this 1949 note summarizes Rand’s philosophic goal in writing Atlas Shrugged: “My most important job is the formulation of a rational morality of and for man, of and for his life, of and for this earth.”

Following the 1943 publication of The Fountainhead, Rand attempted to write a nonfiction treatise on her moral philosophy, but abandoned the attempt in favor of writing Atlas Shrugged. Rand’s interest in philosophy arose primarily out of her interest in portraying the ideal man in fiction. She wanted to define the philosophical premises that would make such a character possible. Atlas Shrugged and its theme of “the mind on strike” would provide Rand further motivation to develop her philosophy. The novel would combine abstract statement, concretizing drama and the portrayal of new heroic characters.

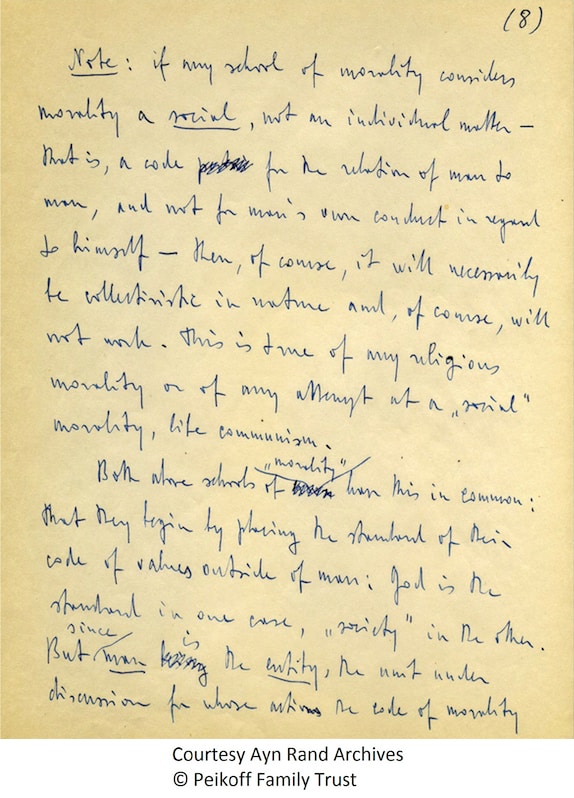

October 6, 1949

October 6, 1949, p. 8

Handwritten notes on Atlas Shrugged

Reproduction on paper

Ayn Rand Archives

This note on the “social” foundation of morality continues Rand’s critique of altruism. By making morality “not an individual matter” but rather “a code for the relation of man to man,” morality collapses into collectivism. Collectivists fail because they place “the standard of their code of values outside of man.” This criticism applies to both “religious morality” (e.g., Judeo-Christian) and “any attempt at a ‘social’ morality, like communism.”

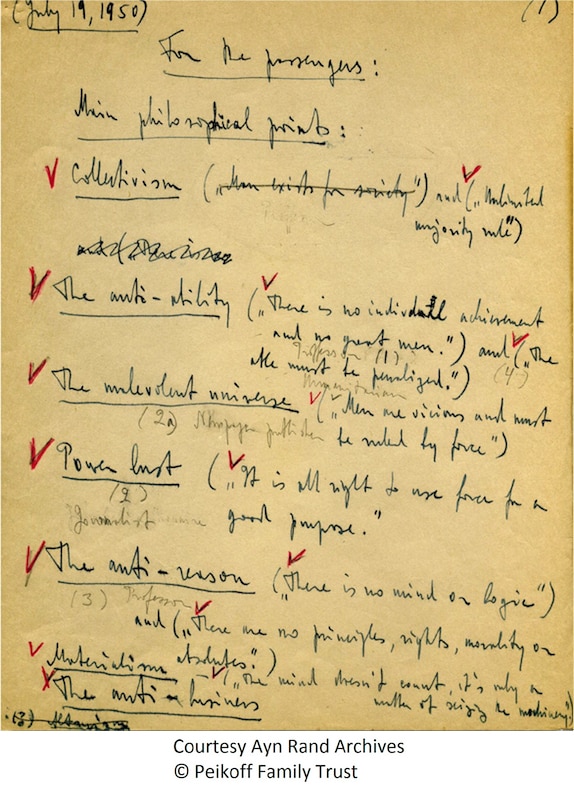

July 19, 1950

July 19, 1950, “For the passengers:

Main philosophical points,” p. 1

Handwritten notes on Atlas Shrugged

Reproduction on paper

Ayn Rand Archives

In preparation for writing a sequence describing a train accident, Rand noted the philosophical views of the victims. Included among them are: “collectivism,” “anti-reason,” “materialism.” As depicted in the novel, the accident is shown to be a consequence of these views put into practice. The sequence is a dramatic illustration of the practical, life-and-death nature of philosophical ideas.

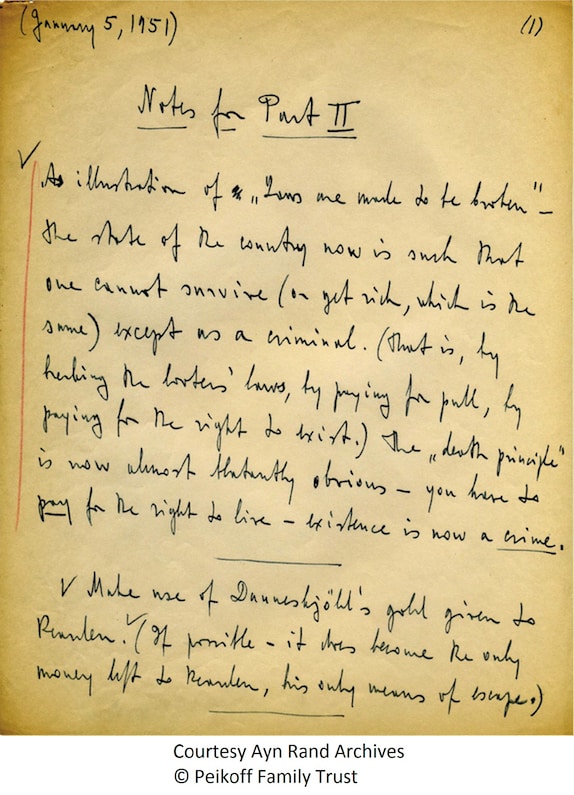

January 5, 1951

January 5, 1951, Notes for Part II, p. 1

Handwritten notes on Atlas Shrugged

Reproduction on paper

Ayn Rand Archives

This note discusses the “death principle” of altruism and its expression in economics. The thinkers, the industrialists and creators in every field face a fundamental threat from the “looters’ laws.” Governmental controls over the entire economy have effectively criminalized every action necessary for human survival. The regulated economy depicted in the novel demonstrates altruism’s contempt for human life. “You have to pay for the right to live — existence is now a crime.”

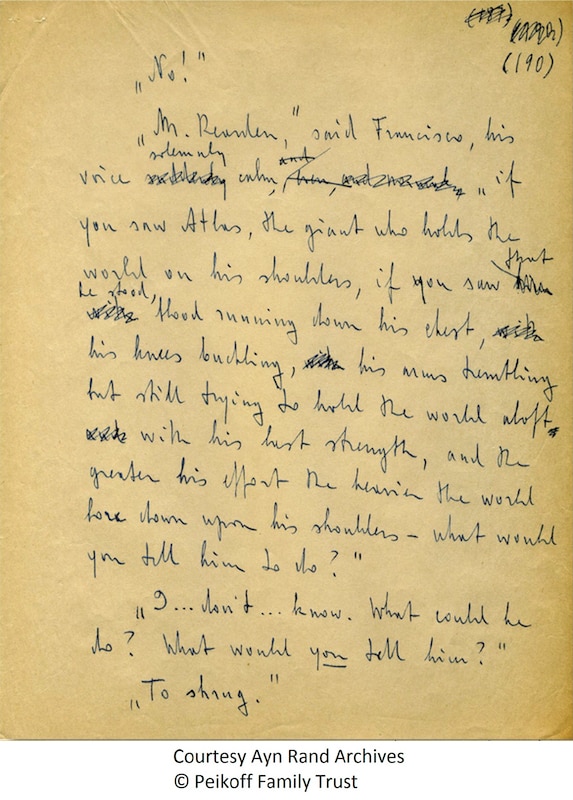

Undated manuscript

Undated, p. 190

Handwritten notes on Atlas Shrugged

Reproduction on paper

Ayn Rand Archives

From an early draft of the novel — this page of dialogue dramatizes both the theme of the novel and Rand’s final title. Hank Rearden, an industrialist struggling under the world’s moral code, listens to Francisco d’Anconia, a former copper magnate. The decision to “shrug,” and thereby let the world fall, requires a moral sanction — a sanction permitted by a radical, new code of morality. Rearden’s discovery of this new morality is dramatized in the remainder of the novel.

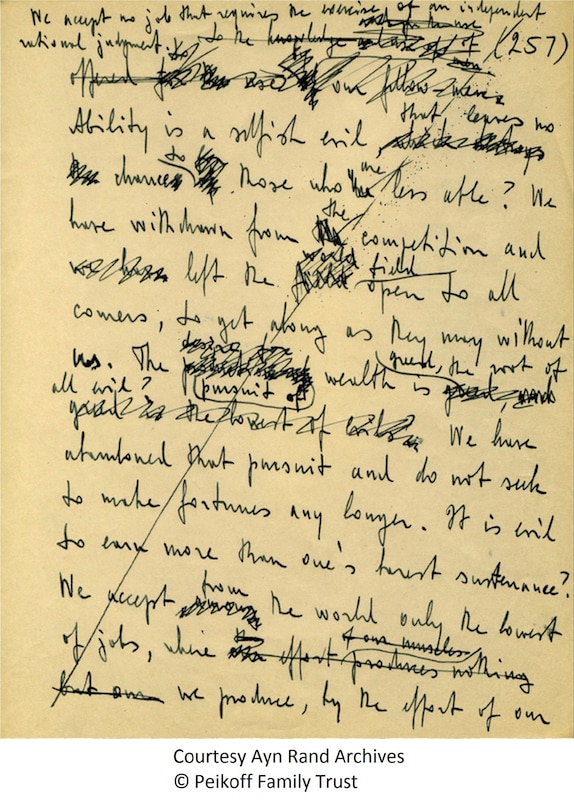

Undated manuscript

Undated, p. 257

Handwritten notes on Atlas Shrugged

Reproduction on paper

Ayn Rand Archives

At this point in the novel, John Galt, the novel’s main hero, is revealed as the originator and force behind the strike. In this passage Galt explains how a strike by the men of ability merely complies with the world’s moral code. He states:

We accept no job that requires the exercise of an independent rational judgment. Ability is a selfish evil that leaves no chance to those who are less able? We have withdrawn from the competition and left the field open to all comers, to get along as they may without us. The pursuit of wealth is greed, the root of all evil? We have abandoned that pursuit and do not seek to make fortunes any longer.

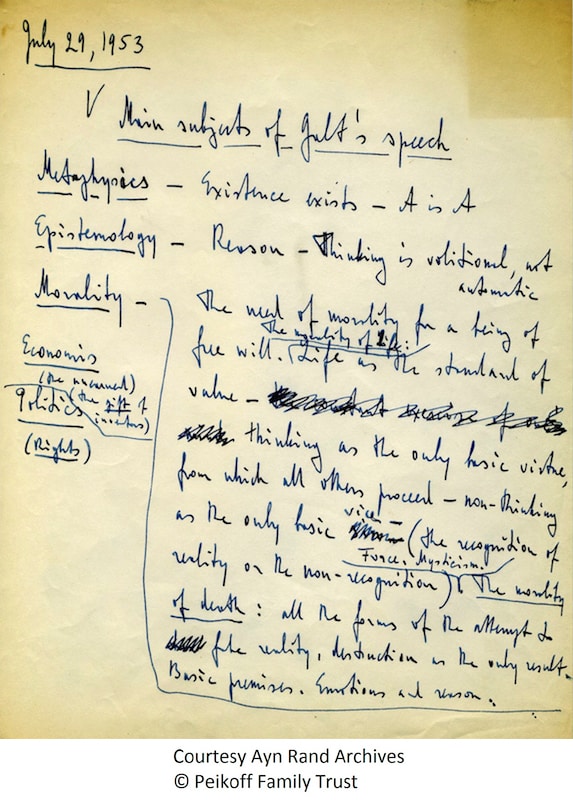

July 29, 1953

July 29, 1953, Main subjects of Galt’s speech

Handwritten notes on Atlas Shrugged

Reproduction on paper

Ayn Rand Archives

This note outlines the main subjects of Galt’s speech, a 35,000 word summary of Rand’s philosophy and its morality of life. The outline here covers four branches of philosophy: Metaphysics (the nature of reality); Epistemology (the nature of knowledge and its validation); Ethics (the good); Politics (the nature of a proper social system). She also lists economics, which is not a branch of philosophy. In her speech Galt explains the moral foundations of a capitalist economic system.

Rand’s defense of the prime movers

“required that she formulate her own views on numerous philosophical issues, including the origin of values, the nature of volition, the law of identity as the bridge between metaphysics and epistemology, the finitude of space and time, and the nature of universals. When a philosophical issue arose during the writing of the novel, she would think about it for several days and then, in one or two attempts, resolve the problem.”

(Ayn Rand, by Jeff Britting, 2004)

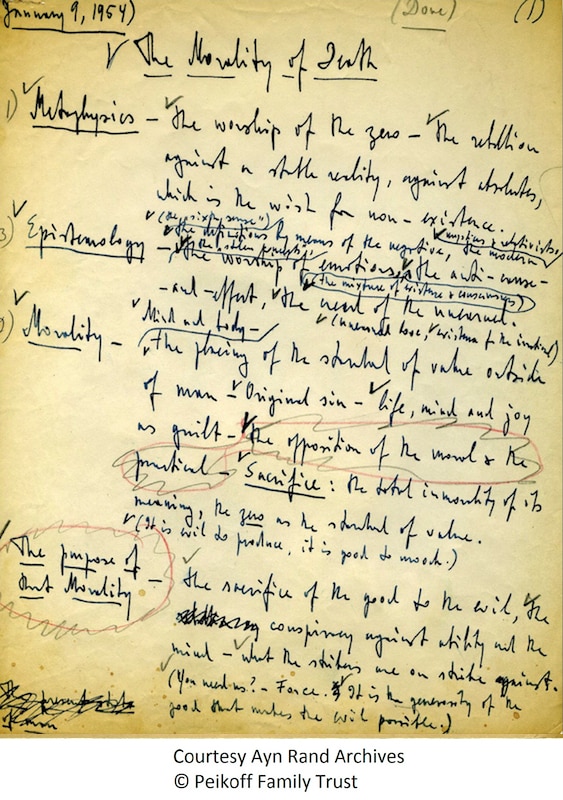

January 9, 1954

January 9, 1954, The Morality of Death, p. 1

Handwritten notes on Atlas Shrugged

Reproduction on paper

Ayn Rand Archives

In an earlier note from Atlas Shrugged, Rand wrote that evil “cannot remain stationary: it must either be eliminated entirely or it will grow (like ‘a few’ controls in a free economy.)” In this 1954 note created during the writing of Galt’s Speech, Rand analyzes the full flowering of evil in philosophical terms. In its final form, the speech will attack original sin, the soul-body dichotomy, sacrifice and altruism.

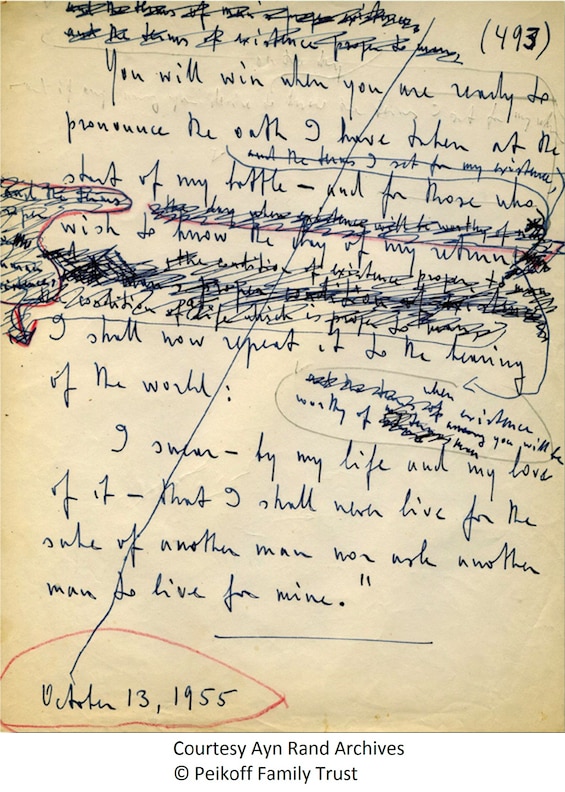

October 13, 1955

October 13, 1955, p. 493

Handwritten notes on Atlas Shrugged

Reproduction on paper

Ayn Rand Archives

This 1955 draft is the earliest extant, final page of Galt’s Speech, which includes the oath taken by all the strikers:

I swear — by my life and my love of it — that I shall never live for the sake of another man nor ask another man to live for mine.

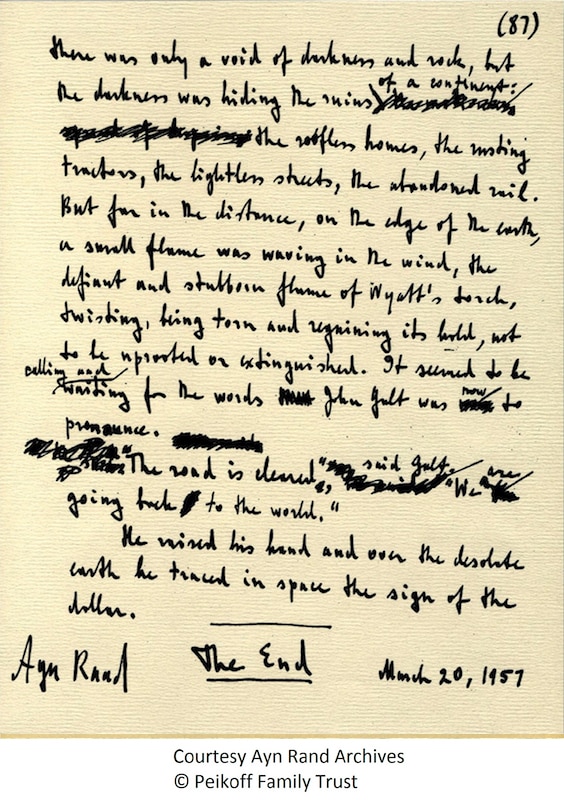

March 20, 1957

March 20, 1957, p. 87

Handwritten notes on Atlas Shrugged

Reproduction on paper

Ayn Rand Archives

This 1957 page is Rand’s last and final handwritten page of the novel. The work had taken almost fourteen years to complete. As to Ayn Rand’s personal reaction to completing the final page of the manuscript, she recounts:

I was too dazed, in a way, to remember anything except walking into the kitchen and Frank [O’Connor] was there, and I held the last page, with the words, “The End” and the date on it.

* * *

After the publication of Atlas Shrugged in 1957, Rand devoted her life to writing nonfiction, explaining her philosophy and its applications to the culture and current events. Rand directed her effort towards human beings and their need of “a philosophy for living on earth”:

In order to live, man must act; in order to act, he must make choices; in order to make choices, he must define a code of values; in order to define a code of values, he must know what he is and where he is — i.e., he must know his own nature (including his means of knowledge) and the nature of the universe in which he acts — i.e., he needs metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, which means: philosophy.

Objectivism, as she explained it in her first Los Angeles Times column in 1962, advocates reality, reason, self-interest, and capitalism. “Reality,” she wrote, “exists as an objective absolute — facts are facts, independent of man’s feelings, wishes, hopes or fears.” Reason is man’s only source of knowledge and guide to action, and his basic means of survival. Survival requires an ethics of rational self-interest, where every man “must exist for his own sake, neither sacrificing himself to others nor others to himself.” Politically, this requires laissez-faire capitalism, a complete separation of government and economics, where the only purpose of government is to protect man’s individual rights. In esthetics, she wrote, art is a concretization of “metaphysical abstractions,” and she defined a theory of “romantic realism.”