“Je Suis Charlie” No Longer: A Year After the Attacks, Is the West Betraying Free Speech?

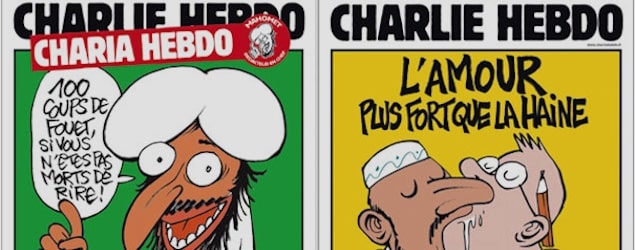

One year ago today, Islamic terrorists entered the offices of the French publication Charlie Hebdo and fired sixty shots inside of three minutes. When the smoke cleared, eleven employees of the magazine and one building maintenance worker had been killed and eleven other people in the building had been injured. The “crime” for which these individuals were being punished was blasphemy. The magazine had offended Islamists by publishing images of Muhammad. It had done so often over the years, but Charlie Hebdo’s satire was not aimed exclusively at Islam. The magazine was an equal opportunity offender. It lampooned Christians, Jews, and many others with equal vigor.

No longer. Six months after the attack, Charlie Hebdo announced that it would stop publishing images of Muhammad. Around the same time, cartoonist Renald Luzier, who drew covers for Charlie Hebdo, announced that he, too, would stop drawing the Islamic prophet.

Can we blame them?

Another Frenchman, Voltaire, is widely believed to have said “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” The line, in fact, comes from a biographer who was attempting to summarize Voltaire’s view, but it no doubt accurately expresses what the French philosopher believed, and it certainly reflects the spirit of the Enlightenment in which he lived. Free speech is so important that we ought to be willing to lay down our lives to defend it.

Voltaire and the other thinkers of the Enlightenment were well aware that free speech, and its corollary, free thought, are essential to a free and civilized society. They lived at a time in which the Western world had only recently emerged from centuries dominated by superstition and brute force. It was a world ruled by the earthly interpreters of imaginary creatures — “gods” — that they claimed had granted them divine authority to treat the rest of humanity like sacrificial animals. But because superstition and force produce nothing but death and destruction, that world was marked by crushing poverty, sickness, violence, despotism, and perpetual war. That is the world to which the Islamic terrorists who attacked Charlie Hebdo would very much like to return us.

A world like that has no room for the free thinking individual. He is a constant threat to the popes and potentates who live by faith and thus always end up ruling by force. Theirs is a world governed by commandments issued to supplicants and slaves. It requires obeisance and submission. Free thinking individuals do not submit. They question, they discuss, they debate, they use reason to pursue the evidence to wherever it leads them.

To be sure, those who embrace free thought and free speech don’t always produce knowledge or speak articulately. But theirs is the only method that allows us to understand the world so we may reap all the benefits it has to offer. The last 300 years are a testament to what freeing man’s mind from the shackles of superstition and faith produces: health, wealth and prosperity on a scale that the world had never known before. Without the freedom to think and to pursue knowledge, to question prevailing views, to share information, and to communicate our thoughts, the modern world would not be possible.

Free thinking individuals do not submit. They question, they discuss, they debate, they use reason to pursue the evidence to wherever it leads them.

Still, as important as free thought and free speech are, it is one thing to say you will risk your life to defend them, but quite another actually to do so.

The employees of Charlie Hebdo did so. No doubt, risking their lives was not their goal. But years of death threats and a bombing in 2011 had to have made them aware of the risk that continuing to publish images of Muhammad carried. Still, they persevered.

Now they have stopped publishing those images. Their editor, Laurent Sourisseau, denies that the attacks last January had anything to do with the decision, but that defiant claim, sympathetic though it is, does not ring true. He insists, almost as an apology, that the magazine will still criticize religions, but that is rather like saying one will continue to criticize malcontents without singling out those who are committing murder. The current issue, published to commemorate the attacks, gives us a glimpse of what he means. The cover depicts a blood-spattered generic God with an AK-47 slung over his shoulder above the caption: “One year later, the assassin is still out there.” While there is certainly ample reason to criticize all religions today, the fact remains that it is the Islamists who regularly sling AK-47s over their shoulders and shoot innocent people. Most of the other religions have a long and bloody history behind them, but today, it is only the adherents of the Islamist movement who are waging a jihad against the West and putting to death those who flout their dogmas. And, of course, it was the Islamists who threatened Charlie Hebdo and finally made good on those threats. The one year anniversary of that attack would seem an odd time to decide that all religions are equally responsible for that sort of violence.

The reluctant conclusion to which I’m drawn is that Charlie Hebdo has been frightened into muting its criticisms. It claims the right to criticize all religions, but there seems little doubt, as its decision not to publish images of Muhammad shows, that it will no longer exercise that right with quite the same zeal that it once did. Islamists have succeeded in blunting Charlie Hebdo’s pen.

I’ll ask again, should we blame Charlie Hebdo for this decision?

To answer that question, let’s consider the moral landscape in which the publication operated. Start in 1989, when Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwah against Salman Rushdie for allegedly offending Islam in his book, The Satanic Verses. The Bush administration muttered some words of protest, but neither it nor any other Western nation took any action in response. Rushdie has lived in hiding ever since. That was the Islamists’ first victory in their perpetual war against free thought and free speech. It would not be their last.

Most people are familiar with the major incidents: Theo Van Gogh, the Dutch film maker, murdered in broad daylight in 2004 for making a film that offended Islamists; Ayaan Hirsi Ali, his collaborator and an outspoken critic of Islam, threatened with death in Van Gogh’s attack (in a note pinned to Van Gogh with a dagger) and forced to live under tight security ever since; the Danish cartoons controversy, in which Muslims the world over erupted in protest after a newspaper, Jyllands-Posten, published a number of cartoons depicting Muhammad; the 2010 plot against the creators of South Park for showing Muhammad dressed as a bear in an episode of the show; Molly Norris, who left her life as a cartoonist in Seattle and went into hiding after she became the subject of death threats for initiating a “draw Muhammad day” in response to the South Park controversy; and, of course, the attacks on Charlie Hebdo last year, and, a few months later, the attack on Pamela Geller’s draw Muhammad contest in Garland, Texas.

But these are only a few of the threats and attacks on those who have spoken in ways that offend Islamists. How many people know that Kurt Westergaard, who drew perhaps the most infamous cartoon in the controversy — the one showing Muhammad wearing a bomb instead of a turban — was attacked in his home by an axe-wielding Muslim man who evaded a surveillance system and hacked through a door while Westergaard babysat his granddaughter? Westergaard escaped injury by retreating to a safe room that had been built for just that purpose. Who remembers Lars Vilks, the Swedish artist who drew a picture of Muhammad’s head on a dog’s body? Police foiled plots to kill him in 2010 and 2014, but Vilks was again attacked by gunman while participating in a forum about free speech at a cafe in Denmark. He escaped unharmed, but two people were killed and several others were wounded. That shooting happened in February, so it was lost amidst all the attention devoted to the Charlie Hebdo attacks.

Islamists have succeeded in blunting Charlie Hebdo’s pen.

And how many people know that Flemming Rose, the editor at Jyllands-Posten who decided to publish the cartoons did so as part of an issue devoted to examining self-censorship after he learned that the author of a children’s book on the life of Muhammad could find no illustrators willing to draw the prophet? All the artists solicited were unwilling to risk becoming the next Rushdie or Theo Van Gogh. Who is aware of the recriminations Rose faced after publishing the cartoons or the fact that Ayaan Hirsi Ali was effectively driven from her adopted homeland of Holland after a controversy developed over whether the government should provide for her security, and everywhere she lived, neighbors complained that they feared for their safety? Rose provides many more examples of threats, self-censorship, and appalling appeasement and fear among Western intellectuals in his book The Tyranny of Silence.

Each of these people were trying to focus attention on an important issue, whether it was the threat to free speech posed by Islamists, the horrific treatment of women under Islam, or the growing threat of terrorism from the Islamic world. What we learned from the controversies they sparked was something just as dispiriting: a surprising number of Western intellectuals and opinion leaders are not willing to defend free speech and many oppose it outright. Governments, too, have been unwilling to defend this important right (or to act decisively against terrorism in general).

Of course, no one is quite willing to admit that openly. But the view that free speech is not terribly important and should typically yield to the feelings of others was present in the reactions to almost every attack. Typically it is conveyed by expressing far more sympathy for offended Muslims than for the victims of Islamist attacks. President George W. Bush took exactly that approach when he rushed to express his concern for offended Muslims after the Danish cartoons controversy and his state department compared the cartoons to racial slurs. “We find [the cartoons] offensive, and we certainly understand why Muslims would find these images offensive.” The State Department added that “Anti-Muslim images are as unacceptable as anti-semitic images . . . as anti-Christian images, or any other religious belief.”

This argument is a dodge. Certainly, there are all sorts of images of racial, ethnic, and religious groups that can legitimately be described as offensive. But in assessing that, one key question is, do they convey something that is true? Images of Jews sucking the blood from Palestinian children or orchestrating a world-wide banking conspiracy are offensive because they are viciously false. But if Jews en mass began invoking their religion as grounds for murdering innocent people and threatening and killing those who criticized them, I would look forward to cartoons showing them with bombs beneath their yarmulkes. Cartoons are a good way to make an important point succinctly, and anyone who engages in terrorism should be criticized (at a minimum).

And the idea that the religious beliefs of any terrorists are somehow out of bounds is crazy. Religion is a body of ideas that is supposed to act as a guide to action, and the religious invoke it as such all the time. If there is reason to believe that a given religion is being used to justify murder and terrorism, then of course we should question, criticize, and even ridicule it and its followers (indeed, given the fundamental irrationality of religion — it is admittedly based on faith, after all — religion should be criticized even when its adherents are not invoking it to commit murder). When certain Christian sects invoke their religion to refuse necessary medical treatment for their children (vaccines, for example), we criticize and even mock them. Why wouldn’t we respond similarly to Islamists who invoke their religion to justify using children as walking bombs?

We saw this same approach after the Charlie Hebdo attacks. First, Pope Francis called the magazine “provocateurs” and suggested that it had gotten what it deserved. “[A] reaction could have been expected,” said the Pope. “You cannot insult the faith of others.” Did he mean that Charlie Hebdo should have expected a hail of gunfire and the murder of 11 employees in response to publishing cartoons? It’s not clear; the Pope’s main concern was expressing sympathy for the faithful whose feelings had been hurt.

Next, a journalism professor, writing in USA Today, argued that the images printed in Charlie Hebdo — those goofy cartoonish pictures of Muhammad — were “beyond the limits of the endurable” and therefore “fighting words” that were not protected under the First Amendment. His legal argument is wrong, but notice the implicit view that any Muslim viewing these cartoons could not help but to riot and kill.

If we mock or satirize those who kill innocent people, that is “cultural intolerance.” If we suggest their violent behavior is motivated by the religion they constantly invoke, we are “Islamophobes.” Yet, at the same time, we should know they are prone to violence and assume they will explode at the slightest provocation. But if this is really true, then why is it unjust or irrational to mock and criticize them?

This was a theme that returned time and again after the Charlie Hebdo and Garland, Texas, attacks. Cartoonist Garry Trudeau invoked the image of Muslims driven mad by rage when they saw their prophet ridiculed. He accused Charlie Hebdo of “punching downward” at a “powerless, disenfranchised minority” and thereby “inciting” riots throughout Europe. A group of authors made the same claim when they protested the decision of the writers group PEN to present an award for courage to Charlie Hebdo, calling the magazine’s criticisms of Islam “culturally intolerant” and “Islamophobic.” The New York Times trotted out the “Islamophobe” epithet in a scathing editorial after the Garland, Texas, attack that was primarily aimed, not at the terrorists, but at Pamela Geller, who organized the event. Writing in Bloomberg, Harvard law professor Noah Feldman argued that Geller was morally responsible for the shootings because it was foreseeable that they would occur. Indeed, the possibility of a shooting was certainly foreseeable, which is the reason Geller hired security guards at the event — who, we should be happy to note, did their jobs very effectively in dispatching the attackers before they reached the building. But keep in mind that the attack was foreseeable only because this is how Islamists act. Feldman’s argument amounts to what James Taranto of the Wall Street Journal has referred to as the “assassin’s veto.” The more likely it is that your opponents will attack you, the more morally culpable you are for exercising your right to criticize them. As a result, you should just shut up.

To summarize these critics’ views is to illustrate just how vicious and absurd they truly are. If we mock or satirize those who kill innocent people that is unjust “cultural intolerance” or “punching downward” at a “powerless minority” (not so powerless that they are unable to kill those who offend them, of course). To suggest that their violent behavior is motivated by the religion that they, themselves, constantly invoke to justify their evil deeds is to indulge an irrational fear. Yet, at the same time, because everyone knows the Muslim world is prone to outbursts of violence, we are obliged to predict that some of them will explode with rage at the slightest provocation. But if it is really true that many Muslims are so prone to violent outbursts, then why is it unjust or irrational to mock and criticize them?

Muslims, under this view, are like a pack of wild animals. Taunt them and you are sure to get mauled. It’s not their fault; that’s just how wild animals behave. Indeed, it is worse than this. If we were dealing with wild animals, we would not be criticized for saying so. With Islamists, we are supposed to know that they are dangerous, but we are not supposed to admit it, because that would be “culturally intolerant.”

This is, of course, rubbish. Muslims are as able to make rational choices as anyone else. If they choose to commit terrorist acts, they should be held accountable like anyone else would be. Those among them who condone terrorism or violence should be held accountable as well, at the very least, by being criticizing for their views, including their religious views. And, yes, that criticism should often take the form of mockery and satire, which are wonderful ways of puncturing bad ideas and the often pompous and irrational individuals who hold them.

But this is not what Western intellectuals have done. They express shock and dismay at terrorist attacks, but their criticisms always come with caveats. “Of course, violence is not justified, but . . .” or “Of course, speech is important, but . . .” Inevitably, the “buts” are followed by “we should expect this sort of reaction” or “no one should criticize another person’s religion.” This means that violence is in some sense justified and freedom of speech does not really mean freedom of speech. It means something more like toleration of speech as long as it doesn’t go too far. That is not criticism of terrorism; it’s appeasement. And it’s not a defense of free speech, but a capitulation to those who attack it.

Should it surprise us, then, that a world-weary Laurent Sourisseau, in announcing Charlie Hebdo’s decision not to publish images of Muhammad any longer, said, “We have drawn Muhammad to defend the principle that one can draw whatever they want[. . . .] It is a bit strange though: We are expected to exercise a freedom of expression that no one dares to.”

I would add: and for which you are criticized for having the courage to exercise.

Let us restate the original question: Can we blame Charlie Hebdo for its decision to stop courting death in order to exercise a right that few others in the media, among intellectuals, and even in government seem to care about and for which Charlie Hebdo was constantly criticized?

The answer is simple.

No individual or group of individuals can be expected to continue exercising a right when they have no assurance that they will be protected from attack when they do. Obviously, it is government’s job to provide that protection, and the growing number of individuals who have been attacked or threatened for speaking out or have given up doing so entirely is a sad commentary on the failure of their governments to protect them. But we must ask why this has happened. It isn’t a lack of resources or something that makes Islamic terrorism uniquely difficult to combat, but a lack of conviction that we, and our values, are worth protecting. Western intellectuals are abandoning the values of free speech and free thought (indeed, all Enlightenment values) and governments, not surprisingly, are following suit.

Values like free speech and freedom of thought will remain common values only if they are treated as such. Part of treating them as values means having the moral courage to defend them. The employees of Charlie Hebdo exhibited that moral courage. They exercised their right to free speech when it mattered — indeed, when most others in the media lacked the courage to do so. This made the publication more than a satirist. In its defiance of the Islamists, Charlie Hebdo became a standard-bearer for the principle of free speech. Far from blaming the publication for anything, we ought to commemorate the attacks on it by praising its employees for bravely carrying that burden as long as they did. That is so no matter what we think of the content or quality of what they publish.

Charlie Hebdo had the moral courage to exercise its right to free speech in the face of grave threats. In its defiance of the Islamists, it became a standard-bearer for the principle of free speech. We ought to commemorate the attacks by praising Charlie Hebdo for bravely carrying that burden as long as it did.

Still, we ought to lament the hit that freedom of speech has taken this year — in the terrorist attacks and the shameful reactions to them in the West, in the failure of governments to protect this important right; in Charlie Hebdo’s decision to stop publishing images of Muhammad; in the animosity toward free speech that college students and many intellectuals increasingly display.

Is there any good news?

Yes. A kind of visceral support for free speech remains embedded in the American psyche as far as I can tell, at least outside of intellectual circles. And there are still many intellectuals who are willing to defend the right to free speech. Flemming Rose remains indefatigable despite living under the constant threat of attack. The same is true of Ayaan Hirsi Ali. Pamela Geller is a tenacious advocate for free speech. Bosch Fawstin, whose drawing won the contest in Garland, Texas, (which you can view on our website here), remains defiant. And we at ARI will continue to fight for this important right.

Update: This post has been edited to clarify the essential role government must play in protecting our rights.